John I. Takayama, MD, MPH, FAAP, Immediate Past President

I was minding my business when suddenly the glass windows and metal doors began to rattle. I tried to stand up but then the floor shook so I sat back down. It was all over in less than one minute and most everyone else who were walking about did not seem to notice. When I opened the “yurekuru” app on my smartphone, I realized that I had just experienced a small earthquake, magnitude 3 on the Richter scale. It was 9 am on June 24, 2019, in Minato-ward, Tokyo.

Disasters can happen anywhere, anytime and probably when least expected. The wild fires of last summer reminded all of us that our daily routines can suddenly change. How can we best prepare, so that we can minimize loss of lives and properties, so that we can overcome potential disruptions and continue to do what we do best, to take care of our patients? This is the first of a series of articles on disaster preparedness this summer.

One way to consider disaster preparedness is to remember the safety instructions that we rehearsed the last time we flew on an airplane. The flight attendants showed us where life preservers were stored and how to inflate them; we were reminded about the location of emergency exits, how passageways would be lit and to leave extraneous things behind when evacuating; and we watched how to put on the oxygen masks, first on ourselves and then on others who might need help. There is a logic behind each of the steps, applicable to any disaster; perhaps most important is that we rehearse them regularly.

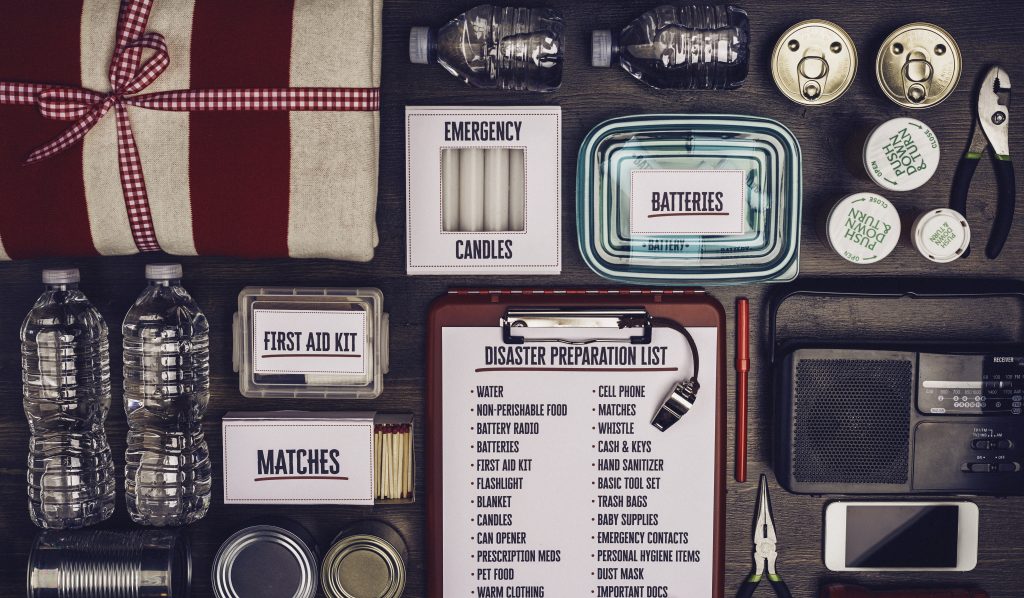

We can also think about disaster preparedness by imagining a particular disaster and what we would do at home, on our commute or at work. In California, likely disasters might include natural ones such as fires and earthquakes as well as those instigated by humans such as gun violence. In natural disasters, preparations might include assembling an emergency supply kit, knowing where our utilities shut-off controls are, planning evacuation routes, and designing a family communication plan. We should participate in disaster drills at least annually, both at home and at our workplaces. Finally, we can include disaster planning in our daily routines, listening to news radio to stay informed about weather conditions and keeping our automobile fuel tanks filled and batteries charged.

I will end here with a description of some smartphone apps that might be helpful.

• CAL FIRE (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection) helps me keep track of my preparations and includes potentially useful tools such as fire maps and wild fire alerts.

• FEMA’s app is more comprehensive and provides disaster preparedness tips specific for each type of disaster and resources that include shelters as well as applications for federal assistance.

• Yurekuru (“shaking is coming” in Japanese) is an app that originated in Japan where earthquakes are common; however, there may be other apps that are more applicable.

Please take our AAPCA1 2019 Disaster Preparedness Survey to gauge how disaste- ready you are; and go to our new chapter website for up to date resources.

Getting Ready

☐ Create a family disaster plan and rehearse it regularly

☐ Assemble an emergency supply kit (include food, water, batteries, contact lists)

☐ Designate an out-of-area contact person (i.e., an uncle, a friend)

☐ Make sure that family members know how to reach the contact person

☐ Know where your gas, electric and water main shut-off controls are

☐ Stay informed; know your local emergency notification and evacuation systems

☐ Plan and practice evacuation routes